Of all the many rally speeches I've heard over the course of the 2011 GE, one that stands out for me is that given by NUH Senior Consultant Paul Tambyah at the SDP's downtown lunchtime rally on May 5, where he points out the dire inadequacies of Singapore's healthcare system and how ordinary Singaporeans fall through the cracks in the events of major illness and disease, due to inexorably costs of medical care.

"You can afford to die, but you cannot afford to get sick", NUH Professor Paul Tambyah said to rousing cheers, obviously striking a common chord with the crowd.

“As a medical doctor, I come into contact with patients on a regular basis. I hear them tell me that in Singapore, you can afford to die but you cannot afford to get sick. I see people who have to sell their homes and move into rental flats to pay for their medical bills. Do you think this is right?”

“The problems with our healthcare system are known to you all – mostly they are about money.”

He further gave an example of the financial burden of one of his patients due to medical costs:

"A Patient of mine has an infection that has caused him a stroke. He needs medication that costs more than $250 a day. There is no subsidy for this medication . It is recommended in all the guidelines including local guidelines. If he does not take this medication, he will most likely have another stroke and could even die."

"I tried to help him by appealing to the medical social worker. We received the reply that he was unlikely to get help as he lives in a private condo with one of his sons. The other five siblings are not well off but this one son living in a condo disqualifies this citizen of Singapore from financial assistance. We even went to the extent of writing a prescription so he could buy his medications in Johor Baru but this did not work."

"How many people do you know living in condos with their own families can afford to pay $250 a day or $7500 a month for medications for three to six months on top of the needs of their own families???"

"There is something seriously wrong with our system."

I agree that there is something very wrong with our healthcare system, and the "can afford to die, but can't afford to get sick" refrain is an often heard one, even my mother said that one before. Quality, timely healthcare in Singapore is expensive, there's no denying. A week's stay at Mount Elizabeth (where wealthy Indonesian tycoons and Saudi sheiks rub shoulders) by my late grandmother racked up a bill in the region of $10,000, but that was no problem because my entrepreneur uncle could well afford it.

But that set me thinking, can my modest salaried income support my mother's hospital bills if she really needed the medical care in the future? Will it bring me and my family to financial ruin? This is a disturbing question to ponder, more so after listening to Dr. Thambyah's anecdote. And I'm sure, I'm not the only sandwiched Singaporean with such concerns.

But before I give my two cents, let me state for the record that having spent my entire working life in Taiwan, I have absolutely no idea how Medisave, Medishield and Medifund work, except that the first one is a paltry number that shows up in my yearly CPF statement. Hence, I will not attempt to make any comparisons.

I will instead give a picture of a healthcare system that I am familiar with and use on a daily basis - the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI), and let you, fellow Singaporean, to judge for yourself the difference between the two systems. I'm not a medical professional, just someone who uses the system, so I don't know what it's like from the healthcare provider's (i.e. the doctor's) point of view. If you're interested in the economics of health care in Taiwan, you can check out this paper.

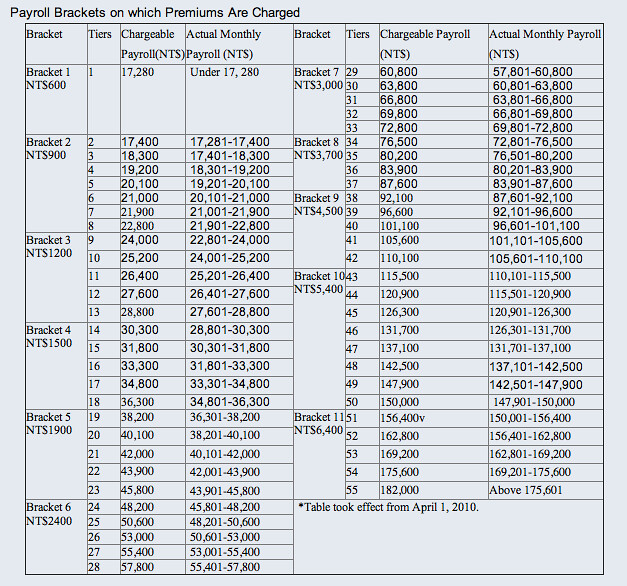

Having lived and worked in Taiwan for the past decade, I've been enrolled in the NHI. In fact, all Taiwanese citizens and permanent residents are enrolled by default and must pay the monthly insurance premiums. So how much premium does one have to pay? It basically depends on two factors - your occupation and income.

Firstly, let's look at occupation. This determines the contribution ratio, or how much the individual, employer and government has to pay in terms of insurance premiums. So if you're an average employee in a public or private company, you pay 30%, the company 60% and the government tops up the remaining 10%.

People in the military, veterans and low-income households get full government assistance and don't have to pay any insurance premiums at all. Self-employed people pay 100% of their premiums.

Secondly, income. Basically, the more you earn, the more you pay. The average adult in Taiwan pays around NT$749 (~S$32) a month out-of-pocket in insurance premiums per person. If you're married have children, you can choose to peg the insurance premiums for your kids to the spouse with lower income to avoid paying higher premiums. An average family of four can expect to pay about NT$3000 (~$129) a month for healthcare insurance.

Okay, so you pay the compulsory NHI premiums every month. What do you get in return?

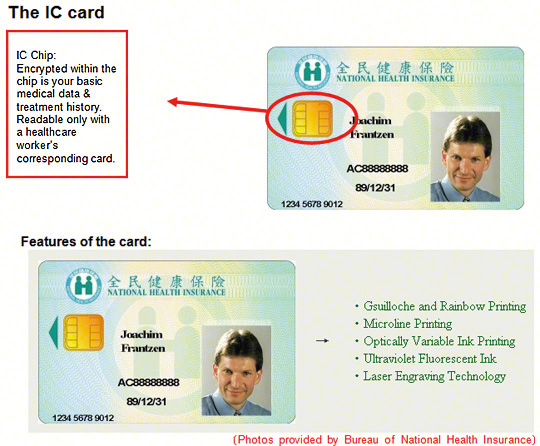

For starters, you'll be issued an IC card by the NHI, which entitles you to seek medical services at any NHI-registered clinic or hospital. The IC card above stores all your medical data and treatment history, so no doctor has a monopoly over your medical records, hence you're free to seek advice from any doctor, knowing that he or she has access to your medical history instantly and can make more accurate diagnoses based on it. Practically every man, woman and child in Taiwan has one. My daughter was issued an IC card on her birth.

In Taiwan, almost every single clinic or hospital, large and small is registered with the NHI. This means you can pick and choose which doctor to see, at your preference and convenience. No need to queue at some polyclinic for hours, because clinics are available everywhere. Only in the event of emergencies (or on Sundays when most clinics are closed) then you go straight to a hospital. If there are queues, people do so voluntarily because they prefer the doctor for some reason, not because they have no choice.

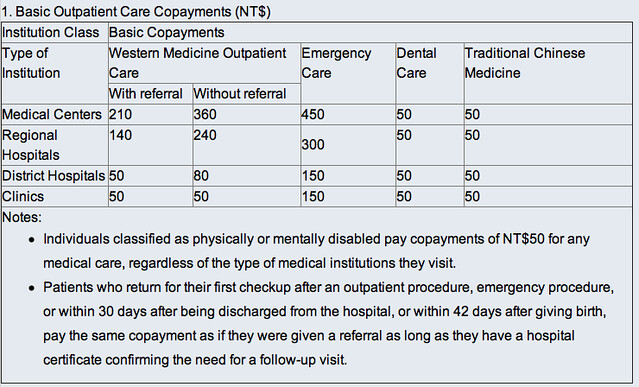

When you see the doctor at a clinic or hospital, you have to pay outpatient charges as a form of copayment, this is to avoid abuse of the system through overuse. For ordinary neighborhood clinics, one usually pays around NT$100 (~$4.30) for a visit (NT$50 for consultation and NT$50 for appointment fee). Disabled people pay a flat fee of NT$50 for medical care no matter at hospitals or clinics. Visits with referrals cost less than those without referrals.

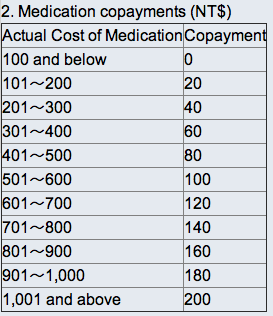

After the consultation, comes the medication costs. For everyday illnesses like flu or cough, usually you don't have to pay anymore for the medicine. Only if the actual cost of the medicine exceeds a certain amount, only then you'll have to make up the difference. Medication co-payments are capped at NT$200 (S$8.60), so regardless if the medicine costs NT$2000 or $10000, you only pay NT$200.

If you have chronic illnesses such as hypertension or diabetes, you are exempted from the co-payments, and are eligible for "chronic illness refill prescriptions", i.e. you can get your medication straight from a pharmacy without having to visit the doctor.

Finally, let's look at coverage. What does national healthcare in Taiwan cover? Besides outpatient care at clinics and hospitals, it also covers:

So what this means that all the major illnesses like cancer and diabetes is fully covered by health insurance. While this means escalating medical costs to the government, it makes a world of difference to the patient, especially those who are disadvantaged to start with.

And there you go. I know it's not a comprehensive report, but I hope it covers enough for you to get an idea of what it's like to be part of an affordable healthcare system. I don't have to worry about exorbitant medical costs breaking my piggy back, because I have an army of decent doctors (many with overseas degrees), dentists and ophthalmologists to take care of me and my family in case anything goes wrong.

Of course, it only covers the basics, so if you want extras like the latest medicine, high-tech medical tests and a single hospital suite all to yourself, you still have to pay extra. But forget the high-end, the rich can afford quality healthcare no matter the price. It's how we take care of the people at the lowest rungs of society that really counts, I feel.